Lit, 2017 Stained stoneware, glazed porcelain. Medieval lead pilgrim badges including ‘Our Lady of Bologna in Crescent Moon’ kindly loaned by Canterbury Museums and Galleries.

Specially commissioned by Sidney Cooper Gallery for the solo exhibition Shell-Lit Siambr. The accompanying publication, designed by Fraser Muggeridge Studio, is available here.

The giraffe invites you to do the same

On the 9th of July 1827, a female giraffe named Zarafa was presented to King Charles X of France as a gift from the Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt, Mehmet Ali Pasha. It was hoped that the gift of Zarafa would encourage the King to withdraw French support for the Greeks, who were at that time fighting the Ottoman empire in a war of independence. Captured in Sudan as an infant, transported on the back of a camel to Khartoum, Zarafa was first shipped by boat to Alexandria, and from there (accompanied by three cows to provide her with twenty-five litres of milk a day) with her head protruding from a hole cut in the cargo hold, she sailed on to Marseilles. She over-wintered in the company of naturalist, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire before beginning her forty-one-day tour North, drawing a crowd of thirty-thousand in Lyon, with a further one-hundred-thousand spectators lining the streets of the capital to witness her arrival. The great Balzac wrote a short story in her honour, commemorative plates, clothes and jewellery were made, women piled their hair in styles mimicking her long neck; no one had seen anything like her.

Zarafa would have been the first giraffe seen in Europe for over 300 years. With their dinosaur height, the implausible geometry of their bodies, large eyelashes and sympathetic down-turning at the mouths; with their loping run, always failing to catch up with themselves, always running a little late, and their sensitive-looking ossicones, presumably tuning-in to a higher bandwidth of air, seeing a giraffe in the flesh must have felt to the people of France like profound proof that the known-world was now navigable, that its mysteries were reachable. Even so, those same mysteries would have seemed no less mysterious by their proximity, which is what makes the gift of Zarafa the giraffe a distinctly poetic act.

Poems, like other forms of artistic language, make clear and tangible that which overwhelms us. They present us with that which cannot be presented finally, reducibly, that cannot be simplified. Poetry, as an artistic language, uses its symbolic ambiguity, its blurred edges and connotative openness to articulate meaning outside of its limits. Put simply, artistic languages bring complexity within reach without resorting to simplification. We can talk and talk in ways that seem relatively productive and straight-forward according to our intentions and understandings, but poetic acts, art acts, serve to remind us that the human mind is only a hopeful lantern, illuminating what it can of our respective realities. And for all the efficiency with which it can configure the self-evident world, when it comes to encountering a giraffe on the street, the inadequacy of self-evident language can easily be exposed. Art is a way of declaring the limits of language, and just like Zarafa, in doing so it makes the world’s mystery reachable, at the same time as retaining it.

Echolocation Curtain, 2017 Acrylic, pastel on canvas. The Soul Exploring the Recesses of the Grave, William Blake, engraving bought from RSPCA shop, Canterbury. Torches made by Gelert – Outdoors company founded 1975, Beddgelert, North Wales.

John Berger writes in ‘Why Look at Animals?’: “(animals) are the objects of our ever-extending knowledge. What we know about them is an index of our power, and thus an index of what separates us from them. The more we know, the further away they are…”.

To bring the complexity of an animal within reach, to march one through a city, or call one to your lap, is like looking into a distorted mirror: the more we know, the further away they are. He continues:

What distinguished man from animals was the human capacity for symbolic thought, the capacity which was inseparable from the development of language in which words were not mere signals, but signifiers of something other than themselves. Yet the first symbols were animals. What distinguished men from animals was born of their relationship with them.

From the very beginning, Berger is saying, animals have been there as symbols of our uniqueness, our difference, because of our distinct ability to speak in symbols and read them symbolically; because we assign the name ‘animal’ we feel that we are not animals ourselves, but humans. And if animals have always been there to make clear and tangible that which overwhelms us, that is, the business of being conscious, alive in language, configured by a system symbolic thought, then their presence among us must have also been part of our first understanding of the poetic. And so it might even be possible to say that the reading of animals was our first poem. Perhaps this is why looking at animals today it does not feel so fanciful to me to think of them as poems.

Certainly at the zoo I am drunk on the animal-poems. There are the elephants, so huge and alive their height and weight should be measured in centuries, and the homely yaks with their grunge haircuts and bad breath…if a yak’s consciousness is there, it is surely deep, hidden, like a bead of glass in the middle of a watermelon, that sometimes rolls its light across the surface of an eye…whereas an ape’s mind is right on the surface, a river, real-time, uncanny, frightening….but not as frightening as the awareness of a big cat whose consciousness seems to be permanently gnawing on instinct, as if a kinder, gentler nature was constantly battling to suppress the bloody, violent habits of a lifetime…especially panthers, who, driven mad by this tension in themselves, retreat and hide away in their huts, sulking…

But this drunkenness is surely just me enjoying the fact that I can read of the symbols of animals, and nothing to do with the animals themselves. It’s all just projection. And doesn’t it feel unfair, arrogant, patronising to project, and view animals as mere symbols of our own symbolic consciousness? And doesn’t it feel unfair to drag Zarafa from Sudan to 19th Century Paris, and unfair to drag her further, into an essay in 2017, to be deployed as a symbol of the human mind’s intrinsically symbolic mechanics. So why do it?

I guess I can cope with this feeling of unfairness because it is familiar to me as a poet. The poetry cliché goes that everything in a poet’s life is potential material, to be cynically exploited and mined, even if it means contriving terrible life choices, and to hell with everyone else, even the animals at the zoo. Of course it’s more complex than that. Poets (or at least the good ones) tend to do more than greedily dredge the daily lake, and project themselves across its surface. There is the hard work of empathy to be done, and the invitation of an imaginative or emotional dialogue to be extended to a reader. How awful it would be otherwise to write and publish a love poem, to simply drag your beloved giraffe through the streets like that.

Lead Scallop Ghost, 2017 Glazed stoneware with onglaze painting, lead.

But the regular rehearsal of symbolic thinking that comes from writing poems over and over again does impact on how you might view the world and your relation to it, which is where this cliché earns its yard of truth. But this perverse specialism for symbolic reading and thinking does not have to come at the expense of your social or political responsibility to others. Self-consciousness about reading the world symbolically might well be an occupational hazard for artists and poets, or even become, through repetition, a cognitive feature of being one, but that same self-consciousness should extend to the symbols that you choose to offer as artworks, and what the act of offering itself might symbolise according to who you are, and the kinds of privilege you experience. Some material is raw.

And I wouldn’t say that it is especially healthy to have a self-consciousness about your own symbolic reading of the world in any case. Just as listening to your heartbeat is likely to quicken it, the mind does not seem effectively set-up for constant self-scrutiny. Poets and artists are not any better set-up for the self-conscious symbolic life they choose, with its raging weather of endless further meanings, they have simply trained towards a specialism in this kind of perversity. This might also explain the cliché of the ‘fine line between creativity and madness’, which must partly be a consequence of holding the stethoscope to your own chest too often. It is, I admit, exhausting and wretched work: solipsistic, isolating, obsessive, antisocial, selfishly self-absorbing, and ultimately unsustainable. If you want to survive long enough to be creatively productive, you have to retreat back into materialist ignorance every so often to recuperate, let a spoon be a spoon, a cat be warm on your right thigh while the evening news configures the terrible lights and shapes inside its oblong. For your mind to survive the world, it must sometimes return to it.

But I often wonder if it is in fact the dissonance between the symbolic life and the other, self-evident life that is the cause of all the trouble. Maybe it’s the feeling that the two lives are falsely distinct from one another that creates the difficulty, and the effort it takes to keep them apart that leads to exhaustion. What if instead we fully accepted that everything was already poetic, already art, and every human thought and act already a poem about itself, or a kind of ceremony?

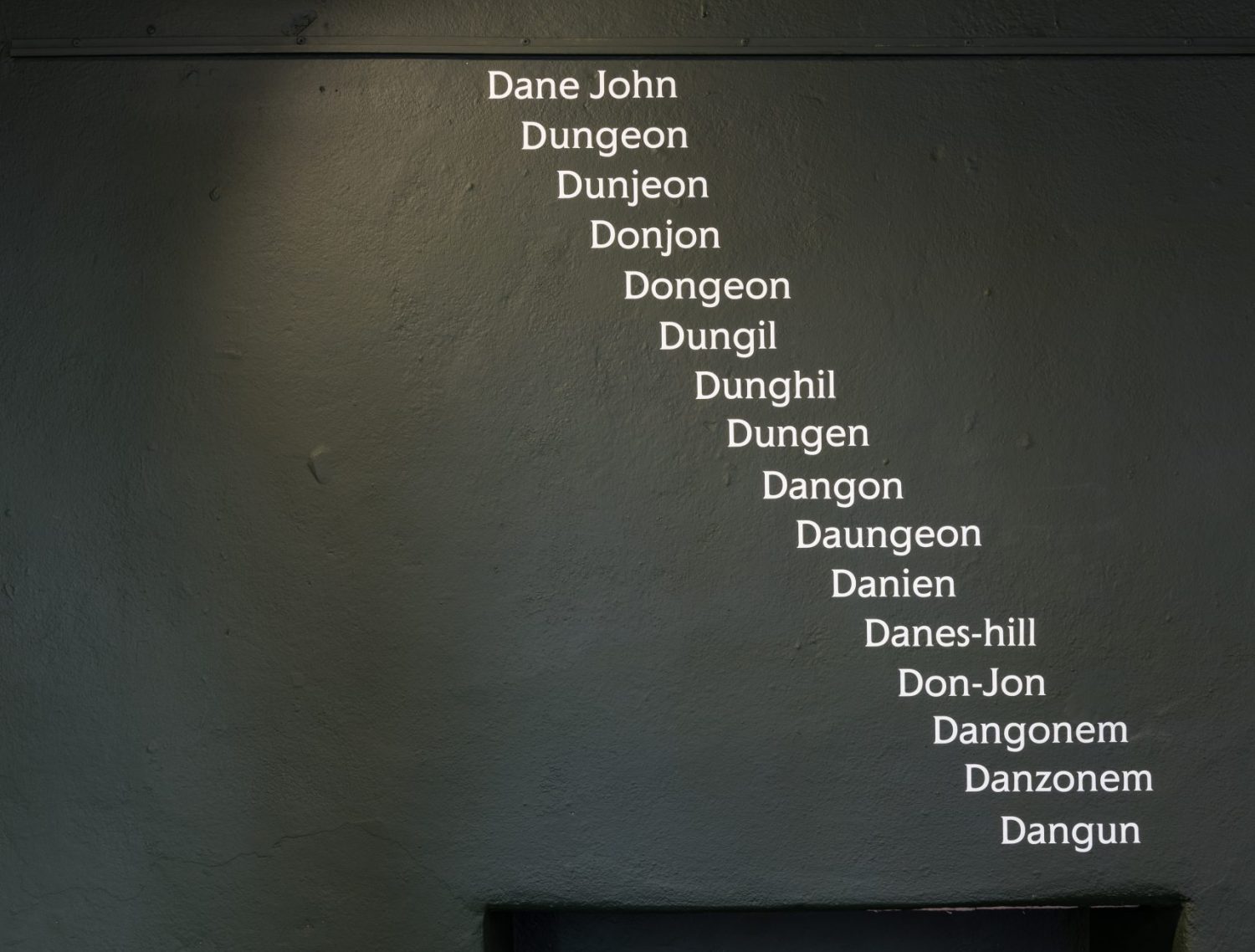

Dane John, 2017. Every historic variant word for an enigmatic Canterbury landmark.

Language relies on constant repetition in time, it is routine: a collective performance of scraping, typing and mouthing the same sound-shapes over and over, in order to keep them meaningful. Why not then call each commute a pilgrimage, or the toothbrush and soap re-arranged by the sink an altar? Why not call each sip of water a poem, a promise, a prayer? Fanciful? Sure. But maybe the seemingly self-evident world could be better reconciled with the symbolic one if we were able to see life as a constant ceremony, and the contingent repetition of our daily acts as a work-song, a language of life, defining itself over and over, for the purpose of its own description.

…I’m forever a child looking out my window at the night sky

Thinking one day I’ll touch the world with bare hands

Even if it burns.

Tracy K. Smith, from ‘Don’t You Wonder, Sometimes?’

I’m not the first to think this, that’s for sure; the burning world presents itself as tactile. ‘Before enlightenment; chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment; chop wood, carry water’, wrote Buddha, while the archeologist Francis Pryor writes of the people of pre-historic Britain:

In the remote past, just as today, rituals were complex affairs, and it sometimes worries me that archeologists seem somehow to view them as straightforward: people made offerings and then got on with their daily lives. In reality, of course, the offerings were an integral part of that daily life and would have been taken very seriously indeed – even if very few of the participants understood the reasoning behind them.

“Dresser” & This Must Be The Place Black clay; needlepoint, Indian ink, pencil, acrylic and wax crayon on linen

Are our lives not still bound up in complex rituals that we don’t understand? Aren’t there all kinds of offerings and procedures that we accept very seriously, without knowing why? The French Marxist Louis Althusser, wrote that ‘In order to exist, every social formation must reproduce the conditions of its production at the same time as it produces’, which is to say that ideology, ‘the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real of conditions of existence’ is not something reproduced from outside by evil overlords, but something that we are all complicit in reinforcing through our daily performance of it in thought and action. We recognize ourselves in the systems and structures we are born into and educated to reproduce and so we agree, almost nostalgically, with the terms of our oppression. Althusser argues that ideology ‘always exists in an apparatus, and its practice, or practices. This existence is material.’ The symbolic language by which we read and understand the world is reproduced by our continual, ritual reinforcement of it in our daily lives, even if, to paraphrase to Pryor’s description of the ancients and their ceremonies, very few of the participants understand the reasoning behind it.

Cover, 2017 Stoneware, needlepoint on linen, lead weights.

But aren’t material daily practices also a potential avenue for emancipatory gestures, for subjective, embodied, poetic or symbolic articulations extending beyond the system? The art historian Omur Harmansah stresses that:

It is important…to situate the embodied individuals in their social, cultural, historical context, without assuming universal generalisations, as Ian Hodder and his colleagues attempt in the context of the archaeological work on the Neolithic inhabitants of Çatalhöyük. Using the richness of material evidence for practices of daily life in domestic spaces, they can start to speak about both discursive and non-discursive practices, ranging from making of a particular wall painting to daily sweeping of platforms…bodily practices in the everyday realm are essentially spatializing and performative: consider the intensive plastering/whitewashing of walls and platform surfaces, embedding of animal parts in the walls, both representationally outstanding and in invisible forms, often routinized but punctuated with special events.

Here Harmansah is framing the ceremonial language of daily life in terms of the theory performativity advanced by philosophers like Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, but most notably by Judith Butler, in her writing on gender: “(…) performativity is not a singular act, but a repetition and a ritual, which achieves its effects through its naturalization in the context of a body, understood, in part, as a culturally sustained temporal duration.”

Situating ‘embodied individuals in their social, cultural, historical context, without assuming universal generalisations’ is surely something you should also try to do when you write a poem or make art for various, unknowable readers, viewers, participants. You can’t make grand assumptions about universal experiences, even while you often call out hopefully to certain shared understandings, but you can ask people to participate in your artwork by bringing their memories, their associative and imaginative faculties into play. Your practice is to make your work a habitation that can allow for such multiple, endless, unique, subjective and embodied participations. I think it is often the case with poems that you realise that while a reader might be entering the space you have made for them, how they move around it, what draws their particular interest, or becomes especially significant or productive by its relation with to the world they have known, is not within your control. In fact, you tend to build your habitation precisely with this loss of control in mind; this is what I referred earlier to as ‘the hard work of empathy’. A poem isn’t a strictly- guided tour, or a linear system of fixed increments. Instead it self-consciously calls backwards and forwards, accumulates, overlaps, swells, frays. The logic is one of metonymy, curation; a poem creates a field, a network, a space for dispersive imaginative participation. One cute fact to remember is that the word ‘stanza’ that describes the little chunks of a poem arranged on the page, comes from the Italian word for ‘room’, which might seem like an analogy for constraint, but I prefer to interpret it as an understanding that poems are houses to enter and occupy, just as houses can also be poems, that is, performative sites of repetition, ritual and ceremony.

Install view, Shell-Lit Siambr

As a writer or artist you are always the first reader to enter the house you are making, and during that time which can be minutes or months, sometimes years, you can be aware, I think, of your physical relationship with the work. It might be that you have carried a phrase, a feeling, a certain urgency through your day, long before you reach the point at which you are at work, embodied, typing, making mouthing something quietly. At this point you might be most aware that you are occupied by and are occupying the poem, but the process of house-building is really indistinguishable from the rest of life, stretching back, your work ‘both representationally outstanding and in invisible forms, often routinized but punctuated with special events’. Now, as you re-read it, alter it, add new lines, arrange it about yourself, you are simply closer to the feeling that this habitation is ready for endless strangers to discover and rearticulate. Of which you are the first.

With all this in mind it is clear that what goes in to a piece of work and what gets left out is more of a case of conscious foregrounding than actual inclusion and omission. A decision might be made to advance the importance of one thing, by positioning it somewhere prominent, say, but that positioning does not make it discrete from the rest of life, which is always on the threshold with its symbols, the connections others will make, the objects and ideas they will bring within reach. Take this piece of text from a mystic website that my research threw-up largely by accident, but has somehow stayed the course in my mind:

Giraffe meaning encompasses the far reaching aura of the Giraffe. Giraffe has great mystical powers as it draws us in with awe and wonder. The regal neck reaching high as if reaching for the stars, as it slowly raises it’s [sic] head it is a rising star in the field of infinite diversity of life…The call of the Giraffe is to rise above the crowd, to trust your instincts. Just as the Giraffe can see far into the horizon as it is the tallest of all animals, the Giraffe invites you to do the same.

This is hysterical, clichéd nonsense to me, and nothing to do with anything as far as I know. But I can’t help but think of the person who wrote it and how, brought into this new arrangement their daily rituals have become part of the practice that produced this text as well. Their weird symbolism is part of my ceremony too, which was already a complex affair, with all my symbols for my symbolic mind arranged materially, but also indicating elsewhere and inwards, reproducing the conditions of my production at the same time that I produce myself, even now, with my new giraffe meaning, that encompasses the far reaching aura of the giraffe, whatever that is, and invites you to do the same.

Jack Underwood

References Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” Why Look at Animals? London: Penguin Books, 2009. Butler, Judith. “Preface (1999)” Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge, 2007. Harmansah, Omur. ‘The Unbound: Performativity of Bodies, Spaces, Things II’, Architecture, Body and Performance, https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/ architecturebodyperformance/848.html (accessed 16.08.17). Love, Presley. “Giraffe Symbolism & Meaning: Shoot for the Moon and Land Among the Stars” Universe of Symbolism: Symbolism, Totems, Spirit Guides, http://www.universeofsymbolism.com/giraffe-symbolism.html (accessed 16.08.17) Pryor, Francis. ‘The Longevity of Ceremonies’ Home: A Time Traveller’s Tales from Britain’s Prehistory. London: Penguin Books, 2014. Smith, Tracy K. “Don’t You Wonder, Sometimes?” Life On Mars. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2011.

Photography, Shaun Vincent